Educating Your Supply Chain

In his book Diffusion of Innovations1 (1962), Everett M. Rogers presented his now famous categorization of adoption of innovation, labeling the different ways we approach new products, ideas and technology. He called us: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Pretty straightforward: the venturesome, the open minded, the masses, the masses who drag their feet a bit, and lastly those who seem to live under a rock.

Rogers says that venturesomeness is almost an obsession with innovators. Their interest in new ideas leads them out of a local circle of peer networks and into unknown territories of technologies and ideas that have been barely tested. It resonates quite close to what the so-called ‘NewSpace approach’ is, or claims to be about. So, let’s dig a bit into that.

The NewSpace ‘ecosystem’ (is there such a thing?) is largely populated by products and services which are still immature. I know, product maturity is a slippery metric. If you read the bibliography on product maturity, it mostly focuses on product/market fit maturity. Here, with product maturity I refer more to the technical side, so we can operationalize it as a mixture of: verification&validation maturity, documentation maturity, incorporation of lessons learned, tooling maturity, support maturity.

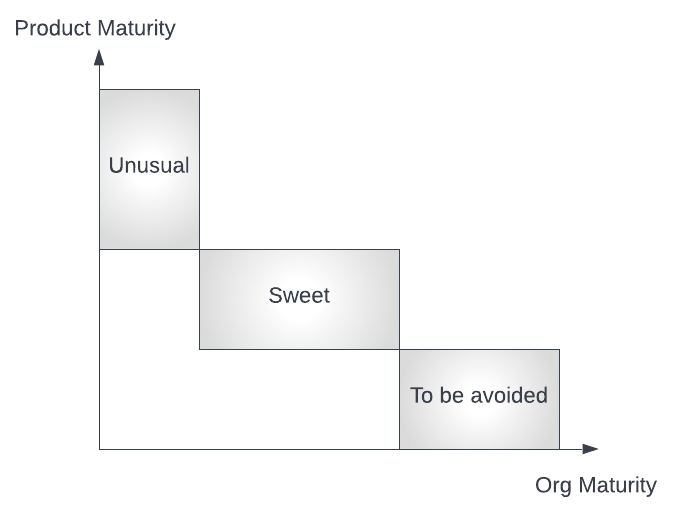

Mind you, product maturity is not necessarily attached to the company’s organizational maturity, although a correlation is definitely hiding somewhere there. There can be companies with 10 years or more in the game and having immature products, which is definitely a yellow flag. An interesting example of this are the ‘big players’ wanting to wear a “NewSpace” skin and coming up with random things to achieve that. Strong Steve Buscemi meme vibes.

Understandably, it is rare to find recently-established companies with mature products, although there might be hidden gems here and there, which are easy to spot: staffed with experienced people with many rodeos on their backs who founded something after years working for a bigger player. But the most frequently occurring case is the immature, recently incorporated company with immature products; this is the subject of this article.

Product immaturity appears as an interesting business opportunity for systems integrators willing to adopt cutting-edge technology for a lower cost, because the manufacturers are willing to give their stuff for a cheap price in order to gain the infamous “heritage” and increase technology readiness levels. In cases, even at no cost. But, as life has taught us on multiple occasions, cheap can be expensive.

The first, big, big issue with adding immature parts and components from immature organizations is pretty obvious, but one that doesn’t appear mentioned often: supplier education, or the flow of knowledge from the more experienced customer towards the less experienced provider. It might (and will) happen that you ask a particular feature, test or qualification to this kind of supplier, only to get a shrug as an answer. They might have legitimately not thought about it, purposely left that feature or test out because of cost or other reasons, or similar. Years ago, an early-stage electric propulsion supplier delivered their first thrusters to an early adopter customer, but the thrusters lacked all the software ‘business logic’ to be used, which the customer had to implement themselves on their flight software, with all the risks associated. Some other supplier, this time on the attitude determination side, lacked a basic feature: a ‘standby mode’ in their product’s software—a very common feature. “Huh, we didn’t think about it”, was their response. Another one, this time on the avionics side, shrugged and admitted they had nothing when requested about compliance with MIL-STD-883 in terms of ionizing radiation tests procedures on their products.

Reality is that, as a system integrator, you most likely insert yourself in the product design lifecycle of your immature suppliers, and the risks they take by not performing certain tests or not developing certain features filter all the way in to your design. There is nothing particularly wrong with that, but awareness is key.

But, as it happens, time flies. Remember when this early-stage supplier came to you with those puppy eyes and practically begged you to on-board their product? A few years went by, and thanks to the heritage they gained with you, other customers became interested, so now they are closing a big deal with them, and you are not so special anymore. Well, this is business after all. Educating your suppliers means also helping them move across the cartesian graph shown above, which also means you are increasing their chances of capturing new customers. Companies of modest size cannot handle big clienteles—although they might think they can; this is a good subject for another article—so they must prioritize and you might be the one displaced. The moment a supplier you helped2 grow turns its back on you is a powerful moment as a system designer. Cuban poet José Martí warned us ages ago:

The only way to be totally free is through education.

Rogers, Everett M, Diffusion of Innovations. New York, Free Press of Glencoe, 1962.

Granted, you were mostly helping yourself, but still.